Apple's Push for Increased Surveillance: A Move to Protect or Control?

Apple’s photo-scanning system: a heroic shield for children or a Trojan horse for total surveillance? Prepare for the chilling truth behind hidden, unchecked power.

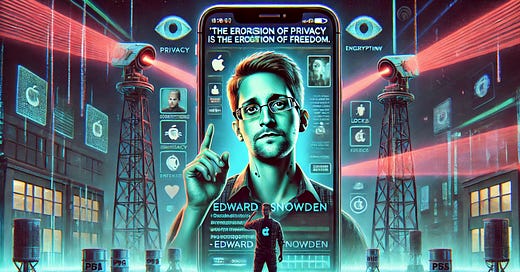

In August 2021, whistleblower Edward Snowden exposed a potentially alarming surveillance initiative from Apple. The tech giant, known for championing user privacy, announced plans to introduce a system that would scan users' photos on their devices before uploading them to iCloud. The initiative, designed to detect "forbidden content" such as child sexual abuse material (CSAM), was framed as a critical step in protecting children from exploitation. However, Snowden, along with privacy advocates and security experts, quickly voiced concerns about the far-reaching implications of this technology. They warned that what begins as a well-intentioned effort to safeguard vulnerable individuals could lay the groundwork for a pervasive surveillance apparatus.

Snowden's primary concern was not the technology's stated purpose but the precedent it would set. By embedding on-device scanning into personal devices, Apple effectively erased the boundary between private ownership and corporate oversight. The introduction of such a surveillance system, once normalised, could easily be repurposed for broader monitoring. Governments, under the guise of public safety, could pressure Apple to expand the scope of "forbidden content" to include politically sensitive materials, ideological dissent, or protest footage. Such an expansion would mark a shift from crime prevention to social control, empowering technocratic forces to enforce conformity and suppress opposition through the very devices people rely on daily.

The Good Intentions Behind the Agenda

Apple's newly proposed system, at its core, is a direct response to an urgent societal problem: the disturbing rise in online child sexual abuse. Tech giants like Apple have a responsibility to safeguard the most vulnerable members of society—children—and prevent their platforms from being exploited for illegal activities. By scanning photos before they are uploaded to iCloud, Apple aims to identify child sexual abuse material (CSAM) and report it to the appropriate authorities. This measure, in theory, stands as a proactive approach to detecting and removing harmful content before it even enters the company's cloud storage service. From that perspective, Apple's initiative can be seen as both critical and commendable: it confronts a severe crisis and attempts to keep malicious individuals from leveraging the cloud to circulate horrific content.

However, as Edward Snowden and other privacy advocates have underscored, there is a very real and concerning "dark side" to such a system. The technology, while currently focused on pinpointing a specific type of unlawful material, sets a precedent that raises significant questions about the scope of surveillance. Once the mechanism for pre-emptive scanning and detection is in place, there are legitimate fears that it could be repurposed or expanded for uses beyond the original intent. Critics worry that such a powerful technology, initially justified by a universally condemned form of criminal activity, could be recalibrated to detect a broader array of "undesirable" or "forbidden" content. This creeping expansion in what constitutes forbidden material would not be unprecedented; history has shown that surveillance systems often evolve beyond their early boundaries, sometimes at the cost of personal freedoms.

The slippery slope, then, comes from who defines what is truly forbidden and how that definition may shift over time. What begins as an effort to curb unequivocally illegal behaviour may gradually extend into monitoring political opinions, cultural expressions, and social movements under the pretence of preserving safety and order. Such an extension could grant authorities a far-reaching surveillance tool, one that can be deployed to quell dissent, marginalise certain groups, or suppress free speech when deemed "threatening." This is not just a theoretical scenario: similar expansions of surveillance have been observed in various contexts around the world, where tools introduced for national security or public welfare were later used to stifle legitimate opposition. Ultimately, the introduction of Apple's new system illustrates a double-edged sword—while it offers a potentially vital safeguard for children, it also opens the door to unsettling forms of monitoring that could undermine the very freedoms it aims to protect.

The Growing Shadow of Technocratic Control

Snowden's dire warnings don't merely shine a spotlight on child protection—they illuminate a crisis that strikes at the heart of our relationship with technology itself. With Apple's proposed system, we see a new frontier where innovations intended to safeguard children could morph, almost effortlessly, into tools of mass scrutiny. The official narrative, of course, focuses on the admirable goal of stopping child sexual abuse. Yet it's that very righteousness that can disarm critics and lower our collective guard, allowing a hidden architecture of surveillance to quietly embed itself into everyday life. A single, seemingly benign concession—scanning data for one "forbidden" category—could become the seed of a far more insidious reality, in which private messages and personal photos come under unprecedented corporate and governmental oversight.

Beneath the polished veneer of corporate benevolence, we find an apparatus built on technical prowess rather than democratic principles. This is the essence of technocracy: decisions made in boardrooms and labs by individuals accountable primarily to algorithms and profit margins, rather than to any electorate or community. Under this model, the potential for overreach is enormous. Consider the seductive power of data analysis—once you have the tools to scan vast amounts of content, the temptation to expand that capacity is immense, be it for "preventing the spread of disinformation," "maintaining national security," or "safeguarding community standards." Each new justification inches us closer to a society where the glow of our screens doubles as the glare of an all-seeing eye, silently judging and cataloguing every digital interaction.

To understand how this dystopian scenario could rapidly escalate, one need only look at history. The Soviet Union and East Germany deployed a labyrinth of surveillance networks to enforce ideological purity, eroding the basic privacy of citizens and normalising constant monitoring. But the tools of that era pale in comparison to what modern technologies offer today. China's expanding system of facial recognition and social credit scoring stands as a sobering testament: an entire population can be kept in check when everyday actions—using public transportation, shopping, or even chatting online—are meticulously observed and calculated. In this light, Apple's system is not just a well-intentioned feature—it's a potential framework for digital dominance, one update or policy shift away from breathtaking intrusiveness.

Worse yet, it's not only governments who might abuse these powerful capabilities. Tech giants, wedded to profit motives and increasingly comfortable operating like quasi-governments in their own right, could exploit surveillance for competitive advantage, market domination, or ideological gatekeeping. With the lines between corporate and state power blurring in an era of privatised data collection, today's "necessary safeguard" can become tomorrow's apparatus for thought policing or consumer manipulation. When corporations like Apple hold the key to scanning our personal files, they effectively position themselves as arbiters of what content—and by extension, what ideas—are acceptable. That role, once claimed, is notoriously difficult to relinquish.

Ultimately, if we are not vigilant, we risk normalising the kind of pervasive surveillance that can snuff out the very freedoms we strive to protect. It's all too easy to dismiss concerns as conspiratorial, especially when child protection is invoked. But safeguarding the vulnerable must not come at the cost of installing a digital panopticon, one that future leaders—and even present-day corporate boards—could twist to stifle dissent, choke off creativity, and punish any deviation from the prescribed norm. The spectre of technocratic overreach is real, and Apple's new system could be the harbinger of a broader transformation: a world in which technological solutions to moral crises pave the way for totalitarian tactics, leaving us with precious little room to breathe, let alone question our new overseers.

The Technocratic Agenda: Surveillance as Social Control

The idea of using surveillance to monitor "forbidden content" fits seamlessly into the technocratic worldview: a society where unelected experts and powerful entities decide what is acceptable, moulding the values and behaviours of the general population. In this model, personal freedoms and privacy are often considered negotiable, sidelined in favour of what is interpreted as the "common good." Governments and corporations like Apple—each wielding its own influence—are increasingly tempted by the allure of digital monitoring technologies, especially when they can invoke the noble-sounding rationale of maintaining security or public welfare. This blend of power and technological prowess is precisely what makes modern surveillance so insidious: it cloaks itself in reassuring slogans, even as it gathers unprecedented amounts of data about our everyday lives.

Once a surveillance framework is established to detect one type of "forbidden content," it becomes disturbingly easy to extend its reach. Today's focus might be child sexual abuse material, but tomorrow's targets could include political radicals, outspoken activists, or virtually any group labelled a "threat" to the status quo. By rebranding or expanding the definition of "dangerous" or "subversive," those who control the surveillance apparatus effectively gain the ability to shape public discourse. This slippery slope doesn't merely erode privacy—it chips away at autonomy, undermining the idea that individuals can hold independent opinions and beliefs without fear of retribution. Over time, a once-free society risks descending into an environment where self-censorship becomes the norm, as people worry that any statement could be misconstrued as unacceptable.

The rise of Apple's new scanning initiative echoes historical precedents in which surveillance technology was weaponised for social control. In the past, governments used wiretaps, informant networks, and other analogue methods to ferret out "subversive" ideas, but the digital age has supercharged these capabilities. Apple's system, under the banner of child protection, could act as a blueprint for even more expansive monitoring in the future. The danger isn't confined to governments alone—corporations themselves can shape social norms by determining which behaviours are permitted on their platforms. And once powerful institutions coordinate their efforts, they can enforce conformity on a scale unimaginable just a few decades ago.

This creates a climate ripe for the regulation of ideas rather than just illegal activities. If child safety becomes the justification for scanning private data, then who's to say a future crisis—be it political unrest or a wave of protests—won't prompt a further broadening of that scope? Before long, individuals expressing dissenting views may find themselves flagged as potential risks to "national security" or "public harmony." Such ever-expanding surveillance can cultivate a chilling effect, where people grow fearful of raising difficult questions or challenging conventional wisdom. Over time, a population conditioned to accept monitoring of "forbidden content" may passively acquiesce to even more intrusive measures.

Ultimately, this convergence of technocratic aspirations and cutting-edge surveillance creates a blueprint for a society where invisible boundaries silently dictate what we can read, share, or believe. Apple's stated goal of protecting children, while noble on the surface, could pave the way for increased invasions into personal spheres—paving a path toward normalising comprehensive oversight. When "forbidden content" can be defined and redefined at will, it opens the door to a world where individual agency is continually curtailed, and where compliance is subtly enforced through an ever-watchful digital eye. If we fail to question the extent of such power or the motives behind its implementation, we risk trading our autonomy for a fragile sense of security—never fully certain which private thoughts or exchanges might be labelled too "dangerous" to exist.

The Broader Implications of Widespread Surveillance

While Apple's move to scan for forbidden content like CSAM might have started with the best of intentions, the long-term implications are much more troubling. The surveillance system not only represents a dangerous precedent for the erosion of privacy, but also opens the door for a world in which privacy is continuously compromised under the guise of protecting society from harm. The notion of "forbidden content" could expand far beyond illegal material, turning surveillance into a tool of social control.

The idea of using surveillance to monitor individuals' personal data is not new. Throughout history, those in power have leveraged technology to monitor, track, and control populations under the guise of security or public safety. The rise of technocratic control—where decisions about what constitutes acceptable behaviour are made by experts, corporations, or governments—has led to an increasingly invasive digital age. The risk is that Apple's surveillance system may be just the beginning of a broader societal trend where technology is used not only to solve problems but to regulate and suppress individual thought and behaviour.

Ultimately, while this initiative might initially appear as a tool to protect children and prevent illegal activities, the real question lies in what happens once the technology is in place—and who will be the ones to decide what content is considered "forbidden." What begins as a well-meaning effort could evolve into a tool for widespread surveillance and control, undermining the very principles of personal freedom and privacy in the process.

BLE mesh network began with the contact tracing years ago.

I went looking for humans broadcasting Bluetooth Mac addresses for a study group.

I ended up finding a GPS surveillance system in my town that is very creepy.

Iphone uses a IBeacon protocol to transfer data.

It appears google and android now use it.

Many people have the 15 minute Getto ID and don't even know it.

I have pointed it out and they say that's life. The price you pay for convenience of owning a smartphone.

Everything you say or do can and will be used against you in the near future as I see it.

hapening now lost lots of suff offmyappledesk top